Individual And Organized Resistance Of Women During The Holocaust

2019, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw, Poland;

MECHITZA

A partition in an orthodox synagogue which separates initiated men from women assisting and sometimes also participating in a service is not a purely symbolic line of division. Only the place is symbolic, so it does not make any difference if the line of marginalization runs in a bus in Alabama or ghetto benches at Polish universities. In a Catholic church, women and men pray together, but the division starts outside the church walls – in a family, army, school, corporation, or system of education. The same pattern holds true for the memory of the universal history of hate. Today, when part of this history is recounted by the community of non-Jewish narrators, it is important to bear in mind that this community has yet to overcome its own divisions.

Collective memory, in particular politically engaged historical memory, is a special and quite non-metaphorical place of division. The Mechitza, which constitutes poetic and vivid point of departure for revising the memory of uncomfortable facts and narratives, is deeply and permanently ingrained in the institutions and tools of writing it down. Accounts and records have a clear cultural and gender bias.

It is essential who comes into possession of the deposit and how, as well as who records, protects and uses it. In our western cultural circle the group of the heritage’s guards and notaries comprises men and those women who agreed to speak on their behalf against the testimony of other women. It is their statement that millions of people are intently listening to.

My artistic practice aims at challenging this monopoly. As an artivist heavily involved in putting archival truths (read: myths) straight, I look for a germ of a new story in them, a herstory, a new archive based on women’s experience of war and violence.

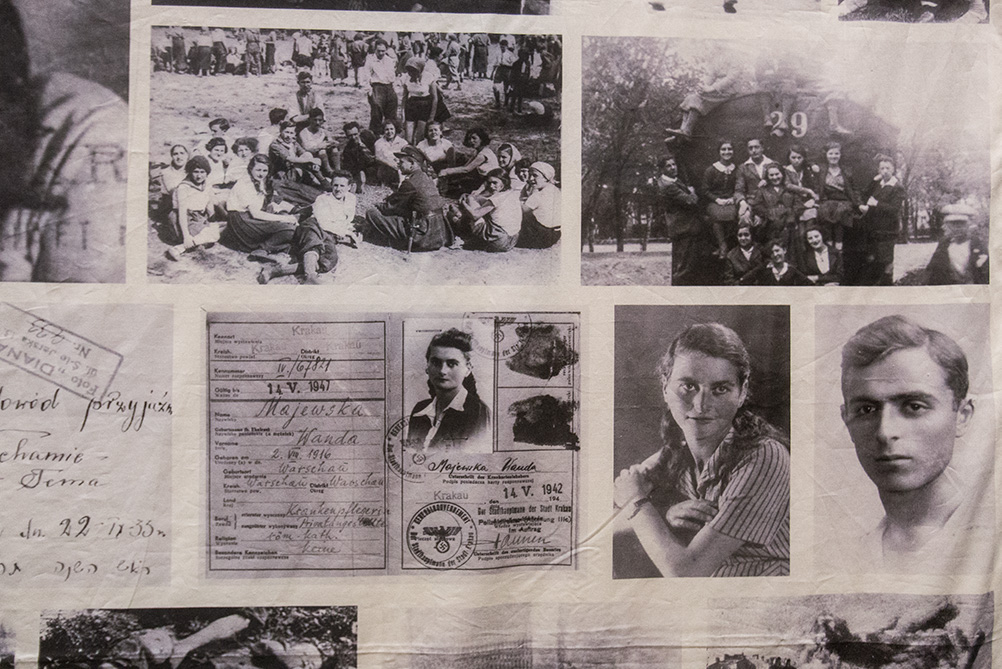

The watershed moment of this new view on the resistance during the Holocaust was represented by my performance at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, when I brought accounts of individual and collective acts of women’s resistance to the fore. Resorting to a purely feminine medium, namely fabric, I wrote down, on cloth symbolizing a mechitza (provided with archival photographs and reports by female witnesses), a history of women’s fight for recording their testimony and preserving it. Against this background, I recounted the story of sisterhood, solidarity and love.

I am becoming part of the retold herstory, I convincingly showed the mechanism of marginalizing the role of women, the game of commercializing historical memory, and the obstacles I had encountered in finding credible testimonies. And I distinctly transferred this narrative to the present day. I take up a story, moving it into the historical moment when it was blocked for the purposes of one-channel narration, in which combatant women were assigned the roles of assistants. I want to resume the story in such a way that it does not die.

Fabric is not only a medium, but also a thread and a warp, a banner. I combine it with the description of the situation of women regaining the right to write their own history. In this history, the accounts of heroines of resistance are to fit together into a uniform whole with the records and artefacts which demystify attempts to obliterate the Jewish identity of women fighting for survival.

A symbolic mechitza, a wall of canvas put in the very centre of the display space, is the central point of the exhibition at the POLIN Museum. I placed, on one side, texts accompanied by archival photographs of militant women. On the other side I embroidered a topographical map of the places in which they organized their resistance.

The Mechitza is a central motif attracting other stories and artefacts connected with the disavowal of memory, evoking the atmosphere of oppressiveness and denial. Not only a symbol, it is a visible sign of the division which, irrespective of geography, still fuels conflicts in our world.